This article appeared in the Winter 1996 issue of "Tricycle" magazine;

The Emperor's Tantric Robes

An Interview with June Campbell on Codes of Secrecy and Silence

An idealistic young Scottish woman goes East to study Buddhism. Twenty-five years later she delivers a radical and unsparing critique of religious structures in Tibet. How much of this system is taking root in West? And how much of it do we really want? June Campbell studied Tibetan Buddhism in monasteries in India in the early 1970's. Subsequently she traveled throughout India, Europe, and North America as a translator and interpreter for various Tibetan lamas. Her book "Traveler in Space" examines the patriarchy of Tibet's political, religious, and social structures, and the real and symbolic role of women in Tibetan society. Today Ms. Campbell teaches women's studies and religious studies in Edinburgh. This interview was conducted by Helen Tworkhov in New York in June 1996. All text in tinted boxes is excerpted from Traveler in Space, available in the United States from George Braziller, Inc.

Tricycle: What was your motivation for writing Traveler in Space?

Campbell: It was a way for me to work through some of the personal confusion that my own experiences left me with. Also, because as time has gone on and Tibetan Buddhism has become more popular in the West, there is much being written by people who know less about the inner workings of the Tibetan system than I, and I thought that what I had to say may be of benefit to others.

Tricycle: Are you referring to the Orientalists' view of Tibet-the kind of Shangri-la myths that still define Tibet in the popular imagination?

Campbell: Yes, but also the academic approach as well, which can take hard lines on certain issues in ways that limit the voices that are heard. Such as the role of women in what is called tantra.

From "Traveler in Space":

Buddhist tantra makes use of the notion that to enlist the passions in one's religious practice; rather than avoid them, is a potent way to realize the basic non-substantiality of all phenomena. The Buddhist tantric deities are invoked and visualized in meditation, and practitioners identify with them in such a way as to enable them not only to be released from the limitations of ego-clinging, but also to transmute the various mind poisons into various forms of wisdom or enlightenment that the deities represent. This is reputed to help break the boundaries between "self" and "other" and ultimately between all dualities that are experienced as part of mundane existence. The highest form of realization is said only to come about through the secret tantric practices that involve sexual relations, and that are depicted iconographically in many religious paintings and images. Among celibate practitioners and the "not-so-advanced," these actions are visualized in the mind during meditation as a way of experiencing the "non-dual" through the images of the dual.

Tricycle: In iconography the male and female forms are complimentary, and the facts speak of an

exchange of equal energies. Yet in your book you portray the institutions of Tibetan Buddhism as

dependent on the subjugation of women. On the other hand, Miranda Shaw, in her book Passionate Enlightenment, speaks of the tantric female masters.

Campbell: But they were all from a thousand years ago; for five hundred years tantric female voices have largely disappeared.

Tricycle: How do you explain their disappearance?

Campbell: To my understanding, it is partly explained by the very unusual social structure that developed in Tibet. Other societies developed kinship, or a monarchy- or lineages that were passed through kinship or, later on, through wealth, or other mechanisms that created a cohesive social system.

The Tibetans incorporated an aspect of Buddhist teachings that had to do with rebirth and reincarnation into the social system, so that you had divine incarnation or what are called tulkus-- little boys--that are identified as being the reincarnations of previous lamas and are born with advanced capacities for enlightenment. In other words: power by incarnation. And these boys are taken away from their mothers and from the domain of the family and raised in the all-male environments of the monasteries. And even misogyny, which was extensive in the monasteries, was used as a way of helping these young men in their practice. In order for patriarchy to survive, women had to be subjugated.

Tricycle: How did misogyny help male monastic practice?

Campbell: In the very popular text of Milarepa's life story-which all lay people and monastics read--there are many expressions of ambivalence about women: how women are polluting, how they are an obstacle to practice, that at best women can serve others and at worst they are a nuisance. At the same time, women are transcendentalized into goddesses, dakinis, female aspects of being that men must associate with in order to reach enlightenment. On the one hand, the monastic boys were cut off from women, from maternal care, from physical contact, from a daily life in which women played nurturing and essential roles, and this whole secular way of life was devalued in favor of a male-only society. And yet these boys grew into practitioners who needed women, either in symbolic form or real women as consorts, to fulfill their quest. So even misogyny, which was extensive in the monasteries, was used as a way of helping these young men in their practice. In order for patriarchy to survive, women had to be subjugated.

Tricycle: Is the tulku system responsible for silencing women?

Campbell: What I argue in the book is that if it is the case that women did once have a more prominent religious role, then it had certainly declined by the time the tulku system was introduced. I argue that early Tibetan Buddhism replaced much of the Mother Goddess worship and incorporated all the female symbolism of the Lotus Goddess into Chenrezig [the Bodhisattva of Compassion]. The tulku system was what put the tin lid on any potential for women to gain equality in the religious sphere, or for their voices to be heard. It ensured the power of the divine male. Women were excluded from the sacred domain, except under conditions laid down by men, and "tantra" was used as a means of polarizing male and female as opposites. As a result, women and their role in the system had to remain hidden. This created very ambivalent attitudes. And in order to keep alive the tantric tradition-as it was being practiced-women had to be kept secret.

Tricycle: Do you mean the actual woman and their relationship to her had to be kept secret, or that their sexual practices had to be kept secret?

Campbell: Both. Because you had lamas who openly had wives and that was quite acceptable. But a lot of them had secret consorts in addition to their wives. And then you had so-called celibate yogis who had secret consorts.

Tricycle: Are the benefits of tantric visualization practices considered parallel to actual sexual engagement?

Campbell: No. They may be presented that way in texts. But in the functioning of the system, to have an actual sexual consort is considered the most important ingredient in the path of tantra. That's where so much of the confusion and ambivalence and misogyny come into play, because you have both: the emphasis on male monastic society and, at the same time the need for women, but without the acknowledgment of the role women play. The centrality of the hidden sexual relationship is terribly important.

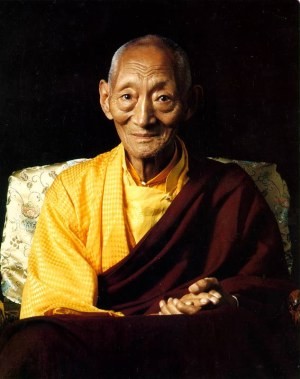

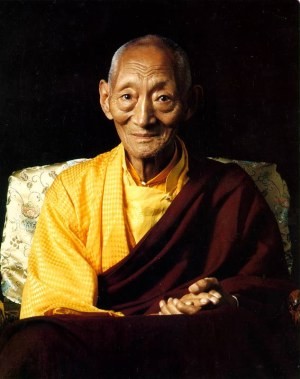

Tricycle: In Traveler in Space, you speak of your own sexual relationship with the late Kalu Rinpoche [1904-1989]. And the revelation was truly shocking to anyone in the West or the East who had known this master. He was considered to be a great Tibetan teacher; who was presented to the world as a celibate yogi. Most of his closest disciples did not know that he had consorts. His secret sexual life seems to have been well protected in his lifetime.

Campbell: When I have asked why details of sexual encounters often emerge after a lama's death I have been told that it is because ordinary people might misconstrue events, and lose faith in their lama, thus breaking their own personal vow of faith in him, and also helping to bring about the lama's downfall. Naturally any fall in the status of a lama who outwardly maintained a position of celibacy would threaten the whole hierarchical system of theocratic rule, itself dominated since the 1500's by monasticism, and as a consequence the heart of the society itself.

The tulku system lay at the center of the monastic way of life, and symbolically depended not only on the exclusion of women, but also on the metaphorical idea of male motherhood and divine succession. Seen in this way, any lamas outwardly transgressing the rules of the system threatened the very life of the system itself.

Tricycle: Is it your understanding that Kalu Rinpoche broke his vows?

Campbell: I don't know what his vows were. We never spoke of them. What I do know is that clearly I was not an equal in our relationship. As I understand it, the ideals of tantra are that two people come together in a ritualistic exchange of equally, valued and distinct energies. Ideally, the relationship should be reciprocal, mutual. The female would have to be seen on both sides as being as important as the male in the relationship.

My relationship with Kalu Rinpoche was not a partnership of equals. When it started. I was in my late twenties. He was almost seventy. He controlled the relationship. I was sworn to secrecy. What I am saying is that it was not a formal ritualistic relationship, nor was it the "tantric" relationship that people might like to imagine.

The etymology of the word tantra is similar in Sanskrit and Tibetan. In Sanskrit, the word means loom, or warp, but is understood as the principle underlying everything.

In Tibetan, tantra is known as ju (Tibetan rgyud), which means thread, string, or 'that which joins things together."

Tricycle: You ended up feeling sexually exploited? Used for personal indulgence?

Campbell: Obviously at the time and for some years afterwards I didn't think this. How could I? It would have caused me too much distress to see it in this light. It took me many years of thinking about the whole thing to see it differently, and to begin speaking about my experience. This wasn't easy. I tried through writing to understand why people rationalize these acts as beneficial, and it made me question a lot of things. I've got no doubts now that when a male teacher demands a relationship that involves secret sex, an imbalance of power, threats, and deception, the woman is exploited. You have to ask, "Where does the impulse to hide sexual behavior come from?" Especially if it happens in a system that supposedly values the sexual relationship. Of course, there are those who say they are consensually doing secret "tantric" practices in the belief that it's helping them become "enlightened," whatever that means. That's up to them, and if they're both saying it, that's fine.

But there's a difference between that and the imperative for women not to speak of the fact that they're having a sexual relationship at all. What's that all about if it's not about fear of being found out! And what lies behind that fear? These are the question I had to ask.

Tricycle: You were sworn to secrecy by him?

Campbell: Yes. And by the one other person who knew. A member of his entourage.

Tricycle: What might have happened if you had broken the silence?

Campbell: Well, it was assumed that I wouldn't. But I was told that in a previous life, the last life before this one, Kalu Rinpoche had a woman who caused trouble by wanting to get closer to him, or by wanting to stay with him longer. She made known her own needs, made her own demands, and he put a spell on her and she died.

Tricycle: Just the way child abusers deal with their victims: "If you tell, something bad will happen to you.

"

Campbell: Yes, there are many similarities. It instills fear in the context of religion. Put yourself in my

position. If I had refused to cooperate I would still have known something that was threatening to the lama and his followers. Where would I have gone from there? If I'd wanted to talk about it no one would have believed me. Some people don't believe me now. And what if I'd spoken out and the lama had denied it publicly? Could he still have been my teacher? I don't think so. As it was I was happy to comply at the time because I thought it was the right thing to do and that it would help me. But I was still very, very isolated and afraid for years to speak about it.

In my own experience, despite the absence of a Tibetan upbringing, there were quite specific motivating factors that helped to keep me silent over many years. These factors were probably similar to those which influenced Tibetan women over the centuries. . . . Firstly, there is no doubt that the secret role into which an unsuspecting woman was drawn bestowed a certain amount of personal prestige, in spite of the fact that there was no public acknowledgment of the woman's position. Secondly, by participating in intimate activities with someone considered in her own and the Buddhist community's eyes to be extremely holy, the woman was able to develop a belief that she too was in some way "holy" and the events surrounding her were karmically predisposed. Finally, despite the restrictions imposed on her, most women must have viewed their collusion as "a test of faith," and an appropriate opportunity perhaps for deepening their knowledge of the dharma and for entering 'the sacred space."

Tricycle: There are Westerners who knew you when you were with Kalu Rinpoche, who were also close disciples. They did not explicitly know what was going on at the time, yet some of them say now that they are not surprised by your book, that they "knew" without really knowing and that the sexual behavior of lamas, so-called celibate or not, is so pervasive that, in addition to their respect for your personal integrity, there would be no reason to question your veracity At the same time, students in the West who never knew Kalu Rinpoche are disputing you story. And I have already received phone calls from two Tibetan lamas in the Kalu Rinpoche lineage asking me not to publish any of your work and accusing you of making all this up, saying, in both cases, "this June Campbell had a fantasy of having an affair with Kalu Rinpoche."

Campbell: Well, it's not the first time that the "fantasy" argument has been used against women. Freud gave in to the social pressures of his day to suppress the truth about what he knew about sexual abuse and incest, and came up with the "female fantasy" theory, now totally discredited. Of course, it's understandable that those lamas should react in this way; after all, they knew nothing of what was going on. But I'd rather face up now to people abusing my character than go on denying the truth. In any case, my book isn't about Kalu Rinpoche. It is about much wider issues than my own personal experience, although obviously the effort to write it came from that experience. I left Tibetan Buddhism thirteen years ago and I spent most of those years thinking about the complexities of what happened. If what I've written is dismissed by Buddhists as irrelevant, or a fantasy, or a lie-so be it, it doesn't bother me. I know that writing the book helped me acknowledge m)r past and come to terms with a lot of difficult feelings. It helped me to understand what happened by myself and on my own terms. No one can tell me that isn't true.

Tricycle: What advice do you have for women who are currently in the position you were in twenty-five years ago?

Campbell: This is a difficult one. Twenty-five years ago I would only take advice from men in maroon robes called "Rinpoche," so I imagine women in a similar position today will be very, very unlikely to listen to a middle-aged Scotswoman, especially one who's just been slandered by Tibetan lamas as being a neurotic liar! Still, you've given me the opportunity, so I'd have to say: Don't agree to a long-term secret relationship; it's a burden you'll have to carry all your life, and in the end you'll have to be true to yourself and face up to why you entered into it. If you're afraid of what might happen next, or how you'll deal with the stresses of secrecy, try to take control of your life again. If you're being passive and compliant because he's your teacher, do as I did eventually: think for yourself, take action, and end it. Never allow part of yourself to be hidden away under threats of "bad karma" or anything else. The truth never made "bad karma." If you need to, look for supportive people to help you. If you've started to feel that in some way you're special, that maybe you've been chosen to fulfill some kind of destiny, well, think again. These kinds of thoughts won't help you to become strong in yourself. They may seem to explain things now, but they'll only hold you back in the long run.

Tricycle: What do women attracted to Vajrayana practice need to know?

Campbell: Well, they need to know that Vajrayana has a long history and social context that is worth studying before submerging themselves in the glamour of it all. That the philosophy underlying so many of the practices is very ambiguous with regard to women's place and role. That if they expect to find an encouragement of women's voices within the system, it'll be hard to find. That there is a lot of emphasis on hierarchies and status. That the system's pervaded by secrecy.

Tricycle: Is there any safeguard, and will it make a difference once the Western heirs have moved to the forefront?

Campbell: It's sad to say but I don't think any advice about standing up to teachers would stop some young women from wanting to have a safe and comfortable relationship with a male teacher and later on being exploited. I wouldn't even bother saying anything to the men who do it. Because they would only rationalize or deny everything or accuse others of all sorts of things. And it's crazy to put all the blame on the Tibetans. It's obvious that Westerners have lots of problems themselves about how to relate to gurus, and we're not exactly perfect in the ways we relate to one another as men and women. What's terrible, though, is that ordinary men and women seem to be happy to give up all responsibility when they know something's wrong and then don't act when they need to. After all: no student, no teacher. I think exactly the same issues would be around for "Western heirs," some of whom might be keen to realize, as Peter Bishop put it, their "dreams of power. "

Tricycle: Is Kalu Rinpoche less enlightened than we thought he was, or do we have to change our

understanding of what an enlightened guru is?

Campbell: It's tempting to stonewall this question altogether because I can already hear howls of outrage and indignation in some quarters at the thought of asking a mere woman about the status of a lama's enlightenment. But I don't think the issue here is about my opinion of Kalu Rinpoche, because, like everyone else's, it's highly subjective and is based on personal experience. I think it's more to do with the problems of squaring up the idea of perfection alongside what is perceived to be dubious behavior. .....................

http://www.american-buddha.com/klosetkalu.emperortantricrobes.htm